This is an average day – at lunchtime – in the city of Barcelona.

Just a few years ago things were different. Our society had many ‘housewives’ whose jobconsisted of doing all kinds of tasks related to taking great care of their home and their families. All of this with no remuneration and, usually, with no holidays.

Today, in many countries, household chores are increasingly being shared more equally among family members.

However, according to a 2017 sociological research study involving 24,006 respondents aged over 21 and carried out by the Yo No Renuncio Association, things are not quite so idyllic.

This study distinguishes between two types of household chores: execution tasks and mental tasks. Execution tasks are delimited and can be measured in time – putting on the dishwasher, shopping for food, taking household waste to different recycling containers, etc.

By contrast, mental tasks are invisible, unpredictable and hard to quantify – for instance, thinking about meals, scheduling your child’s visits to the paediatrician, realising you are missing an important ingredient for your stew, and so on.

The above study does confirm that execution activities are increasingly being shared according to each person’s daily schedule. However, mental tasks are still mainly being carried out by women.

What does this sociological reality mean in neuroscientific terms? This is very clear: women in Spain – and in many other countries – do carry a heavier cognitive load than men. With these tasks requiring conscious attention, their brain cortex has no choice but to consume a lot more glucose.

If we focus on Doing The Shopping (DTSh), it is fairly easy to observe that this activity is usually preceded by thinking or planning what items to purchase.

Thinking is tiring. And also deciding.

Unlike thinking up a list or planning what to purchase, actual DTSh in a supermarket can almost be done on ‘autopilot’ – i.e., with the part of our brain that is active when we do something non-consciously –. So, mental exhaustion is greatly reduced.

When DTSh, this mental load is reduced even more if the store has a ‘everyday-low-price’ policy. Not having to pay attention to promotions (and particularly to their terms and conditions), a customer can pick up the usual products in an automated routine manner, without having to pay too much attention.

On-shelf promotions are mentally taxing for customers, especially if they have to consciously pay attention to them.

Everyday low prices policy is a relief for customer’s brain.

DTSh, both remotely and in store, is an activity that is considered necessary, repetitive, full of frictions and not enjoyed by most people.

Unlike other habits which are pleasure-based, DTSh is a regular routine that is done out of need and lacking in any relevant rewards. As a result, it is something many people would avoid if food were to arrive home through a pipe – like gas or water.

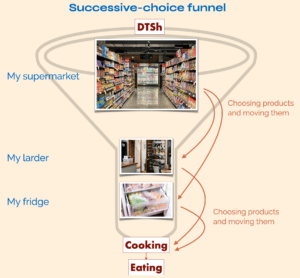

If we visualise the household-restocking process, we can understand it as a successive-decision funnel.

Let us not forget that buying a product in a shop actually involves ruling out other potential options. And deciding what to rule out is tiring.

Buying a product involves ruling out the alternative products that will not be purchased.

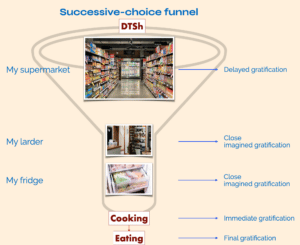

If we now look at this same logistical process but we base it on the gratification each step offers people, we can observe that the further away the task is from a final enjoyment (eating) the less powerful that reward will be.

Psychology clearly teaches us that when a child does something right, the child should be immediately rewarded. And that is how positive habits are reinforced.

DTSh is an activity full of frictions, and the gratification for such an effort will not be arriving until much later.

If we now illustrate the ‘decision funnel’ for someone ordering home-delivered food, we can observe a very different scenario to the traditional ‘funnel’.

Not only involves some deep logistical changes, but there will be a lot less brain cortex exhaustion, as well as an immediate gratification. The desire to have something to eat will be fulfilled within a short space of time.

This will not only generate a high release of dopamine – the pleasure neurotransmitter – but it will also fit with two other sociological factors: a society looking for immediately rewards, and where many decisions are increasingly being left to the last minute.

If we add to that the fact that a restaurant’s choice for delivery is much less varied than that of a supermarket’s, the cognitive load is reduced even more.

Four practical implications

1

DTSh, as it is currently conceived – both because of its significant frictions and because of its limited and remote rewards – is a ‘call for a revolution’. It looks like an ideal breeding ground for some start-up companies that will probably end up being bought by a large chain that now prefers not to do any R&D in retail.

2

It has been demonstrated that cooking – or transforming food – is much better for our health than eating products that are highly transformed. However, that micro-function (cooking) can be done by a different channel player, as long as they are close to the end customer.

Transferring micro-functions between channel players is a way of innovating in commercialisation. It does not matter if any of these were not part of the picture before. I have been sharing this for decades in my Going To The Market course. (If you like, I can send you my ‘Understanding Commercialisation’ notes free of charge).

3

The level of gratification achieved by DTSh will be different according to each customer segment.

I would suggest not to segment by age, gender or even other socio-demographic aspects.

Instead, I would suggest to segment by whether a person looking at a pumpkin knows what dish they will be using it for, or if it simply makes them think of Halloween.

People who like DTSh in the supermarket belong to the segment of those who know how to transform a pumpkin into a delicious soup with octopus skewers, and they enjoy doing so: this is a market segment which is not growing.

4

I do not think the delivery model will be the ultimate ‘winner’ in DTSh, nor do I see it as the best model, when looked at from different angles – such as the sustainability of our planet. But I do understand when Chinese people say to me: ‘At home, we don’t have a kitchen, just a microwave’ – which, by the way, is a very healthy and sustainable cooking tool.

Personal note: I do enjoy cooking. I find it a great active way of enjoying my free time.

© Author: Lluís Martínez-Ribes, m+f=! co-founder and Visiting Professor at ESADE. With the collaboration of sociologist Marina Font, plus the feedback from Rosa Franch and Carla Vallès. BCN, March 2022.

_______________________________

References

Yo No Renuncio Association (2017). Somos equipo. Un paso clave hacia la conciliación. Club de Malasmadres.

https://media.yonorenuncio.com/app/uploads/2021/02/05104456/SOMOSEQUIPO-informe-2017.pdf

Martinez-Ribes, Lluis. (2020). Understanding commercialisation. ESADE and SDA Bocconi. Academic notes delivered at the ‘Going to the Market’ course.

– Should you wish to read these, please send me a message and I will forward them to you. –