583 million results in 0.47 seconds. That’s what you obtain when searching “shopping experience” in Google. It is a hot topic, an expression on everyone’s lips… and as a result, paradoxically dangerous.

Here we shall see the evolution of the concept shopping experience in academic literature and conclude with some practical thoughts.

The playing field

This experience takes place in the store, where many shopping decisions are taken. How many? I’m not sure, as I doubt that a fully validated percentage even exists. If it did, it couldn’t be applied in the same way to people who are doing their shopping (chore) as to those who are going shopping (leisure). In addition, there are two kinds of buyers who represent different situations:

- Those who are replenshing, well aware in advance of what they want to repurchase. They know their products so well, that they spot them at first sight on the shelf, just by their shape or colour.

- Those who make up their mind on the go, based on what they see, read or perceive in the shop. Whatever these end up buying will be much more influenced by what they have experienced in the point of sale than the previous ones. In particular, what shall be influenced is their motivations, beliefs and attitudes.

From 1973 to the early 90s

Philip Kotler (1973) was the first one who claimed that the atmospherics of a shop was a marketing tool. When the design is consciously thought up, it produces emotional effects on the visitor and this increases the probablity of a purchase.

Then, companies in retailing understood the importance of interior and exterior design as a way to stimulate the willingness to purchase. That is, they intended to influence customer behaviour and this aim was their prevailing mindset.

As a marketing tool, the ambience has three main contributions to make:

- If properly differentiated, it draws attention to the shop.

- It is the message. The shop communicates something to the visitor.

- It’s a way of bonding with the shop and its assortment, which increases the immediate intention of purchase.

From the early 90s to nowadays

At that time, it started to become clear that which today is an actual clamor: markets and audiences are increasingly fragmented, and therefore it’s difficult to achieve an effective communication with limited resources. Using the shop as a means of communication could become more cost efficient.

In this context, the main goal was to identify what has most influence on the shopping behaviour.

We can highlight two of the most relevant investigations in this second stage:

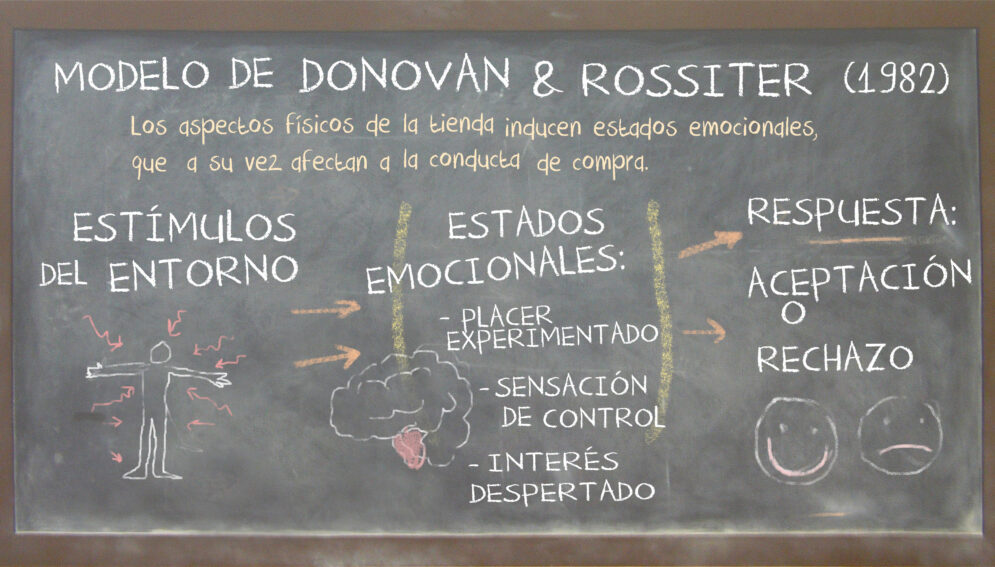

Donovan & Rossiter (1982) studied the works of Mehrabian & Russel in further depth, in order to investigate the responses that certain stimuli would cause on visitors. These are some of their conclusions:

A high degree of novelty and sophistication in the shop creates stimulus and interest.

In appealing surroundings, a high level of interest derives in a larger probablity of positive reaction. Conversely, if the interest and attention of a customer are activated in an unpleasant ambience, the reaction is negative.

That behaviour might also determine the time in the shop, the eagerness to explore, the readiness to talk or interact with other people, the predisposition to spend more money than forseen, the intention to return and the customer satisfaction.

Baker et al. (1992) completed the previous model by classifying the variables of the shop’s interior ambience:

- Atmospherics: music, light, fragrance.

- Social: presence of sales assistants, furniture and customers. An empty store discourages customers… in the same way that a crammed one would.

- Design: both functional (wide corridors, e.g.) and aesthetic.

All these points are of proven relevance, but their combined use hasn’t yet been sufficiently ascertained in order to foresee a given outcome out of each mix.

The shopping experience today

The emphasis is currently put on a shopping experience that expresses the differential sense of the chain brand. Firstly, to draw customer attention, and next, to feel the values of the chain at their fullest.

On the other hand, today the shopping experience cannot be complete without taking into account the internet. Similar guidelines to those of brick and mortar shops can be applied, even if less senses are involved.

It is basic that the shopping experience shows the same brand sense as the retail firm, both in the offline and online shops. The interaction experience must be nearly equal, because digital and physical media are every day more intermingled. (87% of people who buy a car in a dealer have checked them all out on the internet previously).

The players

At the beginning, the first companies that enhanced their customer shopping experience were in the retail business already.

Later, suppliers who saw that many of the purchases were decided in situ awakened and chose either of these two paths:

- To strive to draw visitor attention towards their products in third party shops. Consequently, all sorts of displays and exhibitors have thrived, including sophisticated ones with augmented reality. An avalanche of digital media is now available, yet its focus is in many cases more appropriate for the second stage we mentioned (communication by improved impact) than for enhancing actual brand experience.

- Other suppliers, conscious of the power of multisensoriality but seeing the limitations of acting upong third party shops, have decided to launch their own retail outlets, both offline and online. The examples flourish in every sector and corner of the world. In the mass consumer sector in Spain there are several yogurt shops opened by Danone, and Nestle launched the webside diseloconchocolate.es (tell him/her with chocolate, in English).

In any case, it’s important to remember that communication flows in both directions. Customers now can and want to say things to companies. Thinking about only improving the unidirectional communication just comes to show an obsolete and ineffective management approach.

_______________

Lluis Martinez-Ribes

In collaboration with my former student Aline Adam (MSc Esade).

_______________

Bibliography, in order of appearance:

Kotler, P. (1973). “Atmospherics as a Marketing Tool”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 49, Nr. 4, pp. 48-64.

Donovan, R.J. Rossiter, J.R. (1982). “Store Atmosphere: an Environmental Psychology Approach”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 58, Nr. 1, p. 42.

Baker, J. Grewal, D. and Parasuraman A. (1994). “The Influence of Store Environment on Quality Inferences and Store Image”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 22, Nr. 4, pp. 330

_______________

Source: Código 84, (Burbujas de Oxígeno)