Retail innovation is an extremely hot topic. These three examples speak for themselves:

- A group of experts in retail innovation, of which I form part, received a request from the European Commission for measures to promote this type of innovation across Europe in 2013.

- The last two editions of the Esade programme “Three and a half days’ immersion in retail innovation” (2012 and 2013) welcomed executives from Australia, Korea, China, Switzerland, the UK, the USA, Poland, Spain, Argentina, Puerto Rico and Guatemala.

- A Google search for the term “retail innovation” generates 130 million results.

What is all the fuss about? What is this famous retail innovation actually for?

What innovation isn’t

Innovation is not administration. Innovation is not about keeping business neat and tidy. Innovation is not a question of improving what currently exists. Innovation is not about reducing the company’s weaknesses nor enhancing its strengths. Innovation is not improving efficiency nor winning the game. Innovation is not a matter of obeying the conclusions of a market survey, nor jumping on a bandwagon. Innovation is not a case of detecting and implementing a “best practice”.

What innovation is

Innovation is an exercise of creation, creativity and transformation of the present reality. Retail innovation is inventing a piece of the future that does not currently exist, designing a new way of shopping and changing the rules of the game. Innovation probably involves creating a new trend. Innovation is conceptualising and launching a “next practice”.

The process of retail innovation

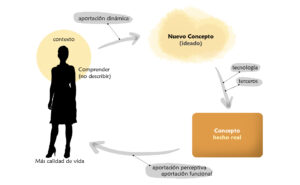

Innovation is not usually the fruit of a single isolated moment, but rather a lengthy process (normally lasting several months) with the objective of achieving a more effective kind of retail. In a market economy, the paradigm of effectiveness is achieved when a customer chooses your store on a constant basis and you are able to benefit from their preference.

From my experience, I have witnessed that this process usually develops best with compact groups, with a heterogeneous mixture of internal and external professionals, with specialists from a remarkably diverse range of disciplines (psychology, biology, neuroscience, sociology) being inserted on a temporary basis. The process is firmly rooted in the customer insights detected in qualitative market research, normally involving projective techniques. Statistically-based surveys does not help to innovate, but rather to monitor an evolution.

The Board of Directors or the CEOs usually get the ball rolling in terms of the process and then provide support later on with decision-making. Without leadership and the explicit conviction of senior management, the process may end up in frustration. This is the reason why the retail innovation programmes at Esade are aimed at decision makers.

Two routes towards innovation

There are two main ways of innovating: technology-driven and customer-centric.

The technological route begins with the identification or possession of a particular technology, followed by thinking of ways to apply it. For instance, developing ways of capitalising on the fact that every smartphone has an IP address, which acts as a sort of registration number.

The customer-centric innovation route takes its inspiration from certain problems experienced by particular customers in order to invent a new way of shopping. To make such an idea a reality, we then search for the appropriate technology. This second route is certainly not averse to technology, as technology enables the solution.

Berger and Bray (2008) demonstrate that customer-centricity and the attempts to improve the shopping experience are powerful differentiation tools.

Whether it goes by the name of “user-driven innovation” (Breuer and Ketabdar, 2012) or “customer-centric open innovation” (Steinhoff and Breuer, 2009), there is an ever-growing number of experts who define a customer-focused approach as one of the main driving forces behind retail innovation (Sorescu et al., 2013). Personally, this is the route that I find most convincing.

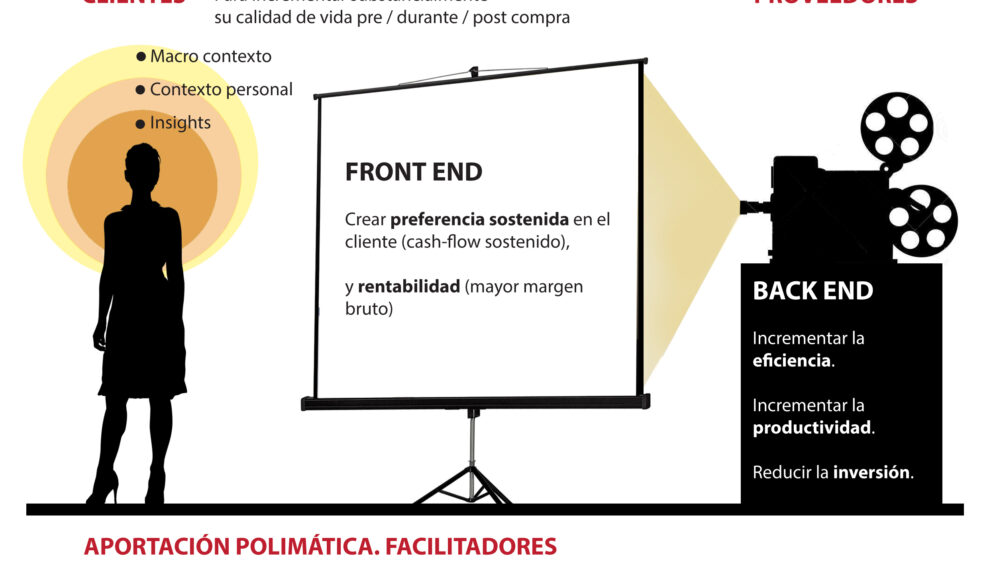

There are two parts to retail

Every retail business model consists of two parts: the part that the customer sees (front-end) and the other behind the scenes (back-end). The latter provides support to the former.

The front-end includes the store (physical or digital), the shopping experience, the product assortment, the services, activities, prices and so on. The back-end consists of elements such as the IT system, logistics, talent recruitment and retention, the suppliers relation’s strategy, the performance monitoring system and so on.

Retail innovation can take an incremental form, applied to a small part of the purchasing process (e.g. incorporating new payment systems). However, the most transformational and effective innovation occurs when the purchasing process is re-engineered, affecting both the front-end and back-end (creating a new retail concept).

When applied to the back-end

If innovation is applied to back-end processes, its purpose is to increase efficiency and productivity, accelerate processes or reduce investment and costs.

The focus in this case is clearly quantitative and it must be designed and implemented by people with the appropriate competencies required in such matters.

For example, innovation based on predictive analytics, taking advantage of big data or data crunching algorithms, is set to be increasingly common in retail companies, as such companies generate immense volumes of data related not only to products but also to people, contexts, etc.

When applied to the front-end

From the customer’s perspective, every purchase is an exchange. They receive a solution (product or service) in exchange for certain efforts that the customer does not like making, but they feel compensated for.

These efforts include all of the bother, problems, concerns, distress, activities and “pains” (including payment) that customers must endure in order to obtain the desired solution.

For instance, the customer’s efforts may involve going to the store, getting there before it closes, parking, finding what they are looking for or asking for assistance, paying and taking the goods home. There are other, sometimes invisible, efforts such as feeling lost or ignorant during the purchase.

Even e-stores involve their fair share of efforts for customers to bear: registering, reading and accepting the purchase terms and conditions, verifying that they are real people by typing strange combinations of letters and numbers, waiting for the order to arrive, etc.

When the efforts that customers have to make when shopping are reduced considerably, they experience a significant increase in their quality of life at that moment.

If innovation is applied to front-end, its main purpose is to provide customers with a substantial improvement of their quality of life when shopping.

The customer’s quality of life does not only improve when they are in the store, but also before arriving and after leaving. The purchasing process, as it is known, involves much more that simply what happens in the store.

From the company in retail

If what the customers experience in the front-end is a more human, emotional and simple way of shopping, the result will be that the store (or e-store) will achieve the customers’ sustained preference (which translates into sustained or increasing cash-flow) and greater profitability (improved gross margin) because customers lower their less price sensitivity.

This is precisely the financial and economic motivation behind the decision of companies in retail to innovate.

There’s talent outside as well

In order to be able to conduct this kind of transformational innovation, it is vital to have true partners that are highly capable, whether they are product suppliers, service providers or external specialists.

Embarking on such a process with only internal resources does not provide the necessary level of heterogeneity and wealth of perspectives, nor does it ensure the diverse competencies required for inventing and creating this piece of the future.

For instance, what would the level of innovation be in Mercadona if it were not for their related suppliers?

In conclusion

Retail innovation inspired by and focused on customers in like a new tree that sprouts from the ground.

It is firmly rooted in empathy, feeling what the customers feel (even though they may not consciously perceive it). The fertiliser that encourages the tree to grow comes from creativity, imagination and leadership. The fruit of the tree is enticing, both for the customers (better quality of life when shopping) and the company (sustained preference and profitability).

_____________

Bibliography

Berger, D. & Bray, J. (2008) “Retail Innovation: The never ending road to success? A critical analysis of pitfalls and opportunities” European Institute of Retailing and Services Studies Annual Conference, 14th-17th July 2008, Zagreb.

Breuer, H. & Ketabdar, H. (2012) “User-driven business model innovation: new formats and methods in business modelling and interaction design, and the case of Magitact”. IADIS International Conference e-Society.

Sorescu, A., Frambach, R. T., Singh, J., Ragaswamy, A. & Bridges, C. (2013) “Innovations in Retail Business Models”. Journal of Retailing. Vol. 87, Iss.1, p.3 – 16.

Steinhoff, F. & Breuer, H. (2009) “Customer-centric open R&B and innovation in the telecommunication industry”. Proceedings of the 16th International Product Development Management Conference on Managing Dualities in the Innovation Journey. Twente, Netherlands.

_____________

Lluis Martinez-Ribes

Source: Código 84, nº 175.