An MBA student from ESADE who was taking my Retail Innovation course (September 2014) mentioned to me that, in Shanghai, several shopping centres have repurposed entire floors, with a shift from stores to restaurants.

(image: artchandising)

There are lots of countries in which retail chains are struggling to keep up sales and productivity, with many cases ending up in store closures. In the United Kingdom, the proportion of empty stores in 2008 was 5%. In 2014, this figure rose to 13.4%, according to statistics from the Local Data Company.

Forecasts in Europe predict a 3.5% increase in conventional retail sales in 2014, compared to an estimated rise in e-commerce of 11% in the same period. This figure reaches 18% in countries in Southern Europe (Reingold & Wahba, 2014, and Enright, 2013).

However you look at it, the statistics show that the retail sector is undergoing a profound transformation for one main reason: customers now buy in a different way. One of the best-known new ways of shopping is showrooming, the cause of so many headaches lately.

As EKN defined them in 2013, these showroomers are “channel agnostic customers” who completely interconnect all of the interfaces or channels.

Showrooming

Warc (2013) defines showrooming as the phenomenon by which customers see the product in a physical store and then buy it online at a lower price.

However, the practice of buying a product cheaper elsewhere was commonplace long before the internet existed. For instance, people often find out about and look at a washing machine in a department store in the city centre and then end up buying it cheaper at a neighbourhood shop.

A second subtle yet important point that is often overlooked by this common definition is that showrooming only becomes a concern for city centre stores when they miss out on the sale of a non-exclusive product. Zara does not worry unduly about a customer looking at an item of clothing in-store and then buying it on the chain’s own app or website.

Therefore, showrooming occurs when somebody checks out a non-exclusive product in a physical store and then buys it at a better price usually but not always online. Bearing in mind the growing number of people using smartphones, it seems clear that this is the great catalyst that has triggered the recent boom in showrooming around the world.

At its root, showrooming is a case of a multi-interface shopping process (physical store, smartphone, tablet, laptop, other physical stores, etc.) that takes place in various contexts (at home, in-store, somewhere outside the home with an internet connection, etc.) [1].

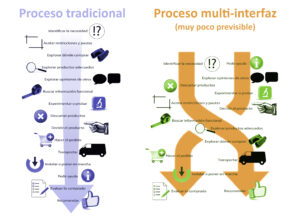

When showrooming occurs, the main activities or functions traditionally performed by customers in the shopping process (see attached diagram) no longer have to happen in this order, nor through the same interface.

(Click to enlarge / image: artchandising)

The fact is that, as a result of showrooming and even more so when smartphones come into play, the shopping process is no longer linear, but rather less predictable and subject to more stimuli that traditional ways of shopping.

Why do customers go to the physical store?

We know from experience that, when we make a decision, two things can happen: we get it right (making us feel good) or we get it wrong (making us feel bad) [2]. All purchases require a number of decisions, including which store to go to, which products to rule out and which one I end up choosing. To reduce the risk of error, we need information.

The information required for decision-making is different depending on the interface (digital or analogue) that is used to obtain it:

| Type of information about: | Analogue media | Digital media |

| Functional aspects (product performance, price, etc.). | Limited information (labelling).

Often higher price. |

The information may be more detailed.

Often lower price. |

| Sensory aspects (user-friendliness, style, weight, etc.). | Perceived with the 5 senses. | Perceived with 2 senses (3 in the case of touchscreens). |

| Symbolic aspects (associations with the chain and the product). | Depends on the case. | Depends on the case. |

We can see, therefore, that stores in which customers can see the product physically have an advantage from the perspective of the sensory contribution, while online stores tend to win in terms of functionality (sometimes with respect to greater information and often with a lower price). In symbolic terms, the influence of the brand has to be weighed up on a case to case basis. This could equally be said for both physical stores (e.g. Carrefour) and online operators (e.g. Alibaba).

The usual way of tackling the challenge

Faced with the reality of showrooming, chains have mainly responded along three lines:

- Penalizing showroomers when they are in the physical store, for example by not offering them WiFi or making them pay if they leave without buying anything. Obviously, this is not the most common solution nor, of course, the most suitable approach.

- Ensuring the exclusivity of the majority of their products. This lets them prevent other stores offering these products and stops customers being able to compare. This approach is often impossible if the chain does not have enormous purchasing power. A slight alternative of this approach involves achieving exclusivity in terms of a small variation of a model, which is given a slightly different code, thereby preventing direct comparison. If this response is feasible, it may be appropriate, but it is often not enough.

- Lowering prices to undercut competitors, especially those that sell online. Although this approach may improve the rate of purchase avoidance, its side effect is a reduction in gross profit and, as a result, the equilibrium point is much higher. If we take into account the fact that costs tend to be higher in a physical store than for their online competitors, companies taking this approach run the risk of making losses.

A proactive approach for city centre stores

The first part of the response is to play to your strengths, in this case, the sensory side of shopping. Turning the store into a launch pad for the imagination (e.g. as Ikea does in certain parts of its stores) and a place that inspires a particular emotion triggered by the simultaneous stimulation of various human senses. Let’s not forget here the important role that sellers play in this respect. All of this goes towards creating a packaging or micro-context, a crucially important aspect of any neuromarketing strategy, as we have seen in earlier articles.

The second part of the response is not only “stemming the tide” but rather facilitating the other part of the shopping experience: being easy to use from an operational perspective. In specific terms, this means enabling customers to access the information through various interfaces. Let me explain.

The information found on a physical label on a product is often insufficient, if the customer wants to feel more confident about their purchase. In this case, the retail chain can offer information on demand, whether that is through interactive screens activated with the product code or with a code than can be activated using the customer’s smartphone.

When the customer uses their smartphone in the store, there are two possibilities: the chain’s app (or website) opens, or this app belongs to a third party. In the ideal scenario, the customer could activate a code on the product shelf to activate a code in the chain’s own app, without having to type anything in. This would give customers more information about both the product and the additional benefits offered by the chain when customers choose to buy from them (e.g. methods of payment, delivery outside the standard timetable, extra warranty, etc.).

Ideally, when customers use the chain’s own app, it shows them something relevant or, in other words, personalized for that customer. For instance, if somebody has a baby, they could be recommended the option of a promotional pack suitable for that context. This would be a case of big data being applied to showrooming.

It is worth highlighting here that anything that reduces the effort required (e.g. easily accessible information, non-technical language, avoiding repetitive tasks such as entering personal details or customer card details again, etc) is likely to generate greater sales.

Moreover, from the same platform, all of the information could be sent to somebody for them to give their opinion, reserve the product and maybe even buy it.

As a third response, albeit complementary to the others, a sales promotion can be added that is issued to registered customers who have given permission for their smartphone to be identified. For instance, customers who spend a long enough period in a particular section of the store could be sent a digital coupon for a certain amount that is only valid for the following half an hour. Technologies such as iBeacon can help, as long as they are not intrusive; the cortex would take issue otherwise.

The result of all this is that city centre store companies have to adopt a multi-interface strategy or an omni-channel approach as it is commonly known. In fact, a more suitable name would be a fully customer-centric strategy, as it offers a complete, personalized experience that is interconnected throughout all of the interfaces.

Operating through all of the interfaces, chains have more opportunities to gather information about customers and, as a result, to general a more enjoyable, personalized and stimulating shopping experience.

John Lewis, a good example

One really good example of the integration between interfaces is the British chain John Lewis, winner of several awards for offering customers an omni-channel experience.

The products in-store have two codes: the traditional one and another in-house one. By scanning the latter with their mobile phone, customers access the product information on the company’s own app. As well as the technical specifications being provided there, customers can also see other complementary benefits that John Lewis offers customers for shopping on their website, personalized discounts generated from previous purchasing data, information on demand and other aspects that make the shopping process easier.

As a result, the chain has managed to establish itself as many customers’ preferred option, even though its prices, while competitive, are not the lowest on the internet.

Finding our bearings

The objective of retail chains is not to prevent customers shopping online, but rather ensuring that they do so using the chain’s own range of interfaces. As Ann Zimmerman (2012) says, competition is not between stores or website, but rather between your website and the rest.

Showrooming is just the tip of the iceberg that shows the deep-rooted transformation that is happening and going to happen in retail, the cause of which is the fact that customers live and shop differently now. Achieving harmony with customers’ lives should be a greater trigger for companies to transform, rather than simply reacting to a rival’s initiative.

_____________

[1] Context refers to the combination of a particular time and place.

[2] For this reason, what people like most is not having to make a decision.

_____________

Bibliography

- EKN (2013), “The future of the store”.

- Enright, A (2014) “U.S. online retail sales will grow 57% by 2018”. Internet retailer, 12th May

- Internet retailer. “European E-Commerce Forecast 2013-2017”.

- Local Data Company (2014) “Vacancy report H1 2014”.

- Reingold, J. & Wahba, P. (2014) “Where have all the shoppers gone?” Fortune, 3rd September

- Warc Staff (2014) “Retailers face the omni-channel gap” Warc, 18th March

- Zimmerman, A (2012), “Can retailers halt showrooming?” The Wall Street Journal, 11th April

_____________

Lluis Martinez-Ribes

Source: Código 84, number 183.

December 2014